It sounds like the name of a secret laboratory: KLM 2030. But Peter Huisman himself calls his office the “KLM candy store”. On the top floor of KLM’s Digital Studio you will find the office that is all about hardware. Here Internet of Things tests are performed, robots configured and machine vision hardware rigged up. And a mess is made. A really. Big. Mess.

On his desk a Raspberry Pi, in the corner a 3D printer, behind it a haptic feedback suit, two toy robot arms and bins full of small electronics along the walls. In the middle of the room, you have to step around it, a man-sized robot runs his test laps. “This is the KLM candy store,” laughs Peter Huisman. His official title is Project Manager Technological Innovation. Together with Marianne IJff and Djim Molenkamp, he runs the “KLM 2030 lab”. ‘This is the KLM laboratory where we play with technology that is not yet widely used at the airline. We are already trying things out that might only become practical in a few years. Or maybe never. Because that is our starting point: “find out what we could possibly do with it.’

Technologies of tomorrow

In that respect, the work performed by the three is not much different from that of the rest of the KLM Digital Studio (DS): here at Schiphol East we are trying to find out what we can do with the technologies of tomorrow, to bring KLM into the new century. That is not a luxury but an absolute must for a company to survive. And with KLM 2030 – known until recently as the Lab of the Digital Studio – it is mainly about hardware where the other projects in the Digital Studio usually revolve around software and processes. ‘Look, this is one of our most recent projects,’ says Huisman while showing a video with passing luggage carts. ‘In the baggage basement it is often unclear what crowds they can expect. To be able to predict that better, we have built a system with machine learning and a few cameras that recognizes what carts are passing by. The system works really well, so you can see exactly what is on the way and what the department can anticipate on. The system is still experimental though. The model we have trained is simple and we use only one camera. But consider the potential of this if you take a bigger approach.’

He points to a large board on the wall with prints that represent a mosaic of projects, there are dozens of them. ‘We actually tackle everything that involves technology and where we see potential,’ says Peter. ‘Our job is not to look at the feasibility in the short term. We go for the long shots, just to see what is possible. Because only when you start investigating something, you’ll see what you can do with it. By that I mean that you sometimes solve a problem that is not the real issue. The real problem then reveals itself, lying deeper in the process. You only discover that if you just get ahead with it.’

Self-driving cart

The projects that the team takes up often present themselves in discussions with colleagues from KLM. ‘We have more than twenty years of experience within KLM and we know a lot of people. For example, the Engine Shop asked us to think about ways in which they can robotize the department. That Engine Shop is the place where KLM maintains jet engines. Such an engine comes in for maintenance and is taken apart and overhauled. But there is more demand for the services of the shop than they have capacity. You can solve part of that problem with technology. For example, it turned out that a lot of data between machines and the computer is being transferred manually by the people behind the machine. They make a print and then type the data into their screen. So we have make the machine talk directly to the computer by adjusting the program code at the hardware level. Keying in data is no longer necessary. That saves tens of hours a month at departmental level. It also turned out that many parts were moved between the different workbenches, that all takes man hours and therefore production capacity. We have now purchased a self-driving cart that can swing between the machines. And because those machines can let you know what time they are ready, the cart can also be there at the right time. We just tested it. I initially thought that the technicians were afraid that their work would be taken away by that robot car, but they loved it. People like change, as long as it helps them with their work.’

3D models

‘Do you know what we have discovered?’ He walks to a large screen and switches it on. A huge 3D model from Schiphol comes into view. Including airplanes and carts. ‘Do you see this luggage cart moving through the image? He actually drives there, now. This is real-time data from Internet of Things sensors, linked to 3D models. You really see everything that moves at Schiphol. And look at this,’ he zooms in on a pier, the complete interior of which becomes visible. ‘Now we can run a simulation of the moment the passengers leave a plane. You see them flowing out, the green passengers are not in a hurry, but the red ones have to make a switch. Do you know what is great about this way of displaying data? It suddenly becomes very concrete. They are no longer numbers, but you get a very clear impression of what is happening. Our field tests show that people who work there can get a vastly better impression of what is coming. Figures in a dashboard are good for the projections of the management. But in the workplace you need 3D visualization. Those are the things we discover with our tinkering. The system is not yet in production, it may take a few years before the spirits are ready for it. But we show that it is possible and what it can potentially deliver. I think that’s the value of what we do.’ All great and fine. But why is it such a mess in here? Peter smiles mildly. ‘We were originally located in another building at the IT department. One of the working concepts there was the clean desk policy. That was awful. Every time I was busy with building something I heard that I had to clean up my mess. But that is not possible at all if you are working on a prototype, we are tinkerers. You have to try things, have parts within reach and be able to mess around. And be able to spread your projects over several days. Cleaning up in those cases works counterproductively. When the Digital Studio was established in 2015, we moved over here pretty fast. Because experimenting is the norm here and nobody frowns at those trays and desks with hardware in our office. We feel much more at ease here. So we can also run better experiments, and that is ultimately why we exist.’

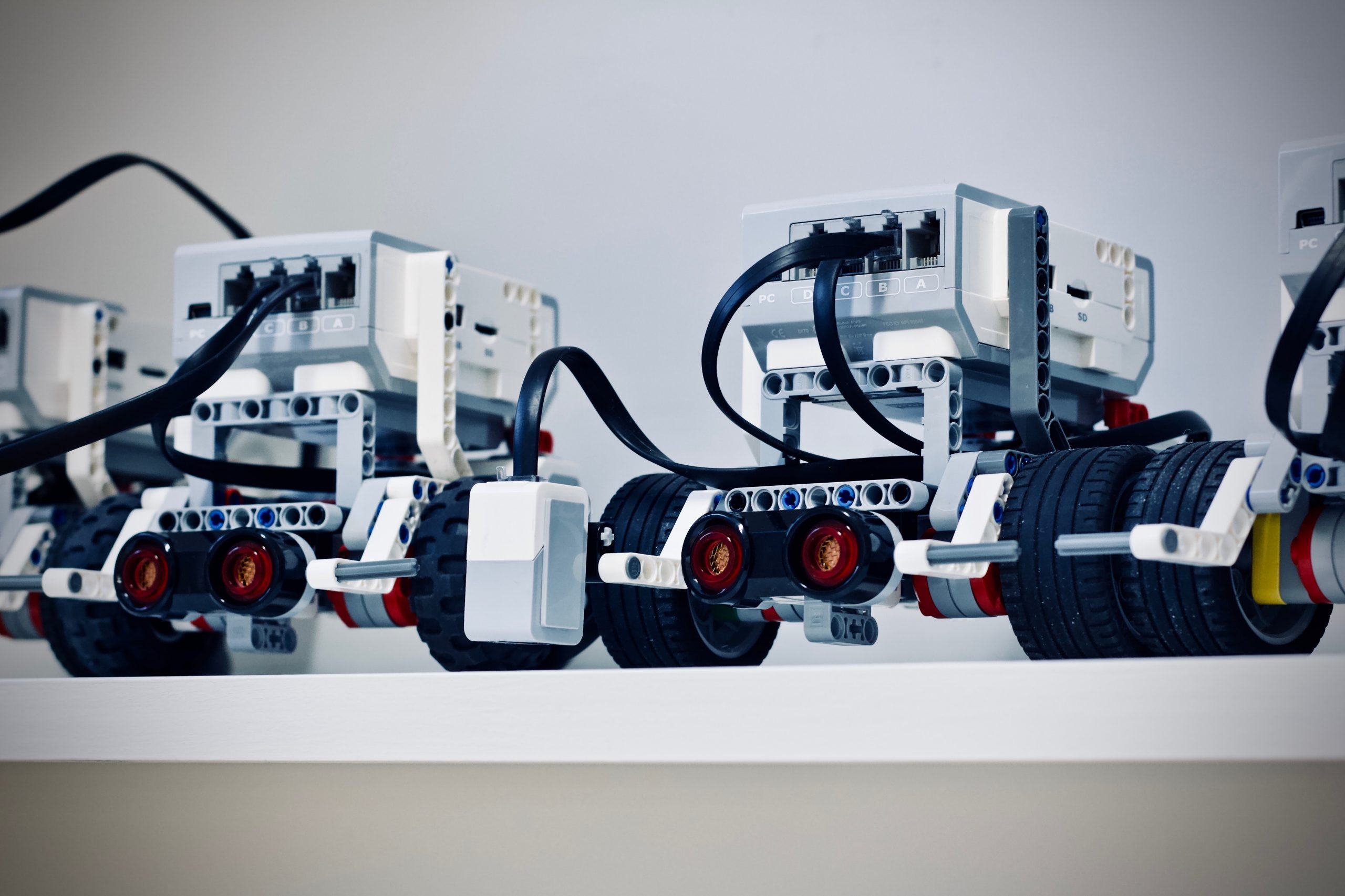

| What does KLM 2030 do? The laboratory of Peter Huisman, Marianne IJff and Djim Molenkamp has been around for six years and has in that time done dozens of short-term projects and experiments. The current projects that they currently supervise include: – Internet of Things Equipment tracking: Where is my material? Experiments with Internet of Things sensors on equipment to track its location. This has resulted in a live business application and service. – RFID for Baggage: Experimenting with RFID on a conveyor belt, demonstrated that RFID integrated in luggage tags ensures successful and correct registration when the luggage comes over a KLM baggage claim from an aircraft. – Self-driving vehicles for the Engine Shop: Experiments with self-driving vehicles within the engine shop to discover how self-driving material can work within existing processes and how people deal with self-driving equipment. – Robotizing the Engine Shop: Experiments to discover what a robotic engine shop could look like, the automation of manual administration, machines that are connected to a central network, and what can you do with it. – Image recognition against food waste in order to better estimate how many sandwiches an aircraft should take on board, it is important to know how many sandwiches are thrown away after the flights. This is now done by weighing them, but that method is too crude. Image recognition and – again – Artificial Intelligence is much better at that. The KLM 2030 team is working on the prototype of the required counting system. |